Sting ran away from his home town, Newcastle, to become a megastar, marry Trudie Styler and have six children. And now he's gone back home. The Times' Chrissey Iley joins him for the ride...

March 11, 2012

Sting: 'I've never been an ideal father because of my job and the way I was parented'...

Sting ran away from his home town, Newcastle, to become a megastar, marry Trudie Styler and have six children. And now he's gone back home. The Times' Chrissey Iley joins him for the ride...

On the streets of Newcastle, Sting's home town and mine, the taxi drivers love him. They like him because he doesn't take himself too seriously. They can joke with him, they say, and reminisce. He's a generous tipper, too. Match that with the multimillionaire whose life revolves between homes in Wiltshire, New York, Tuscany and Malibu. The rock star who likes to talk about the intricacies of Tantric sex and pose topless with Trudie Styler, his wife and mother of four of his six children. The environmentalist famous for saving rainforests and offsetting his rather large carbon footprint. You get a picture of a complicated individual.

Before we get to Newcastle, we meet in Paris. He has some free time between gigs and we talk in a darkly lit hotel room in the Place Vendôme. He's just flown in from doing a show in Vancouver. It's winter. Normally, he's tactile, but today we air-hug because he doesn't want to catch my cold. Jet lag is keeping him awake. "I was praying for the daylight. I was first in for breakfast at 6am this morning. I had porridge and coffee." He looks at me suspiciously again. "I cannot get a cold. I cannot work with a cold. I avoid them by willpower. As soon as I stop touring, I'll get a cold. The adrenalin gets you through a show. A cold is difficult." He sniffs theatrically.

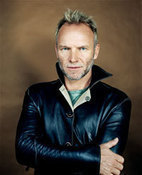

Wearing old cords and a cashmere jumper, he stretches his arms in a yawn and reveals a taut yoga stomach. His trousers drop, showing brightly coloured boxers. "You haven't said anything about my hair," he says with mock petulance. His head is shaved. "I like shaving my head. I'm addicted to it. I like the feel of it."

He runs his hand over his stubble and tells me that women come up to stroke him like a dog, and then he laughs at himself.

"So, here we are, being flagrant," he says. Flagrant is a good word for him. He's a consummate flirt, and he loves to perform. He seems to be on a perpetual tour. Last year it was the Symphonicities tour with the Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, all sweeping keyboards and lush melodies. Now it's the Back to Bass tour, the other extreme: no keyboards, his bass guitar, a couple of violins, percussion. He's touring Europe with it and returns to the UK this month. It's called Back to Bass because that's his instrument and, in the Seventies, he redefined how a rock band should sound thanks to his bass playing.

Is he addicted to being on the road? "It's a lovely feeling. You're out in front of 5,000, 10,000 people and everyone's pleased to see you. It's hard to replace that," he says. "And it's also hard to express how wonderful that feels. Everything seems amplified by the lights and the occasion. Am I addicted to it? Probably. I don't like staying in a city too long. Tomorrow is somewhere else. Let's move."

You wonder, of course, about all this moving about, what it is he's running from. Running has been a constant in his life. He ran from Newcastle to form the Police. He ran away from the Police when they were one of the world's most successful bands in the early Eighties. He didn't tell the band it was over. Perhaps because it wasn't. Years later, in 2007, they reformed. They finally got closure. "You can abandon something; you can never finish it. Relationships are never finished."

He ran from his first marriage, to actress Frances Tomelty. It imploded in 1982 when he fell in love with his neighbour, Trudie Styler. At the time, he thought Styler looked like a "damaged angel", yet he credits her with turning around his life. "She is my orbit. She is my central point. She grounds me. It is important to me that I have something to orbit. Is she a sun or a moon? I don't know."

He's mostly found in New York, where his youngest son, Giacomo, 16, goes to school. "Trudie is based there and I circle her. The circle can be huge, but I have to have somewhere to think of as home, and that's her. She's coming to Paris. We'll go to dinner. I haven't seen her in a month." He exhales loudly, mournfully. "It's hard, but it keeps it juicy. It keeps it romantic. She'd be sick to death of me if I were around all the time." Would he be sick of her? "No," he laughs.

She seems almost an idol to him: the strong woman, the mother, the lover. "She's pretty good at all of those, I have to say."

He seems to enjoy long-distance marriage. Is that because that's how he knows how to feel love, by separation? "Mm," he nods, giving a jet-lagged yawn. "I'm not punishing myself. She does have her own orbit. She has far more jobs than I do. We orbit in tandem, really. But we mentally think each other is home."

The couple were recently shot for Harper's Bazaar – scantily clad, on a bed, kissing, dishevelled. What possessed them? "That was fun!" he replies. "Aren't we allowed to have fun?" He smiles. "There was a lot of outrage and it was just a photo spread. I couldn't take it seriously. We looked good," he laughs. "And that's what annoys other people."

Over 30 years together, their relationship has changed, he says, but they have both changed in complementary ways. "I always encourage her to take on challenges and to work. That's very important to Trudie and me. I never wanted to be going back to the little woman, because I'd be bored by that, but she does so many things. She's an actor, producer, she runs businesses, she edited The Big Issue the other week... She's an incredibly accomplished woman and I'm proud of her. She always steps up to a challenge."

He tells me the ambiguity of love means that Styler could have equally destroyed him as opposed to making him whole. What does he mean? "A lot of relationships begin with an emotional prenuptial where you say, ‘I love you this much, but not enough that I could be destroyed.' That's where a lot of relationships fail. You have to take that risk. You have to give your whole self, everything, so you could be destroyed by it, totally. And the other way, too. If she leaves me, if I leave her." Could that happen? "Of course it could happen. Life's full of surprises. We talk about stuff. We have a deep connection, which we renew on a daily basis. We're not complacent about our relationship at all. It's not that we're insecure – it's just that we know what the reality is. Most marriages end in disaster. It's unusual to have a long relationship and we have a very long relationship. I want to continue it."

It's important to him never to take anything for granted. On the whole, he likes to work at things, be it relationships or songs. For a long time he was devastated about the breakdown of his first marriage. He was quite undone by it, and revisited that sense of loss in his songs. "It's the only thing I've ever failed at." When Sting was Gordon Sumner, bus conductor or tax officer, he worked hard, even though he knew he was a misfit. "I was terrible," he says of the tax collecting. "I was fired and never wanted to work in an office again. I'd also been on the dole, which I hated. I just couldn't do it."

He's just written a musical, The Last Ship, inspired by the life he ran away from when he left Newcastle in 1977. The son of a milkman and a hairdresser, he grew up in the shadow of Swan Hunter, the shipyard on Tyneside. Sting is a contradiction: he wants to move forward, but he's haunted by his upbringing, and it's to those dark places he goes for inspiration. The Last Ship, about leaving Tyneside and coming back, is about a man's need for work, community and love, and about what happens when you take work away. He's written some new songs for it and also uses a couple of moving old ones. His old friend Jimmy Nail, of Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, will star, but it's still early days and he's not sure if it will premiere on Broadway, in London or in Newcastle.

The musical is Sting's tribute to where he grew up, to the people of the North East. "I'm very inspired about it. More inspired than I've been perhaps for a long time. I think it's about what happens when work ends. What happens to communities and how important that is. It's about how people were ambivalent about that job. They think it was a hard job in the worst industrial conditions in Europe, and yet what they built, they were very proud of. They built the biggest ships in the world in that town, and when that disappeared it was a huge thing. That's what the play is about.

"We don't make anything any more. The idea of making things with your hands is important to us, especially men. I work with my hands every night, with an instrument. It's physical work. When you take that away from a community, what do you replace it with? That's the backdrop for the play, but it's also a love story, a redemption."

A few months pass and I go to Newcastle to watch a workshop of The Last Ship. Sting has been in the city all week rehearsing and it takes place in a tiny arts theatre near the Quayside, close to where Sting first performed, pre-Police, with the band Last Exit. In recent years, he's been increasingly drawn back to his childhood home. It started with his 2009 album If On a Winter's Night…, which featured traditional Northumbrian folk songs and the local pipe player Kathryn Tickell; a televised performance was held in Durham Cathedral.

The next day we are at the Malmaison hotel, overlooking the bridges that define the Tyne. Sting has just had breakfast with Jimmy Nail, who calls him Gordon. Does he do that to annoy him? "Yes, a little bit. Nobody else calls me Gordon," he says. "I've known Jimmy 20 years. I can't imagine the show without him. He's very excited; he loves the material and his voice is incredibly raw."

We order espressos. "I was brought up in the shadow of the shipyards. I was fascinated and terrified by them at the same time and wondered where I would fit in. That was the landscape of my dreams. Writing songs for other characters to sing freed me up, and I feel very fertile because of that. You can get paralysed, and I can get in my own way. I hadn't written a song for a long time and in the past year I've written 25. I think you have to write when you feel like writing. When something needs to come out. It's not the kind of job where you just turn it on."

The idea solidified in his head after he read about a shipyard closing in Poland, where a priest began to raise money for a charity to start building ships again to give the men something to do and their dignity back. "It struck me as Homeric – an exciting, crazy idea which actually happened. I thought if I welded that inspiration to the story of my town to make it more allegory than history it might work, and there'd be a good message, a universal message that people need to work.

"One of the most depressing times in my life was signing on on a Wednesday afternoon. I felt demoralised and defeated. I couldn't bear it. I understand what it's like not to have work. I was still a musician. I always had that. Not to have work, it destroys people."

The story is set in the early Thatcher years, which saw the decline of the mining and shipbuilding industries in the North East. "If you have no work and you don't know what's happening next, where's the future? How can we look after our kids? The economic system is falling apart. What do we have left? We have community. The other night, a bloke in the audience said there's something special about Newcastle. There's a spiritual connection with this place. It's not dewy-eyed, sentimental nostalgia. This town is genuinely loveable, with its own river and football team. I don't know another region of England that has this feeling. So coming back, having been away so long, I think I see it more clearly."

He's been walking around the city, exploring the streets that he grew up in with his siblings, Philip, Anita and Angela, navigating a path between what's lost and what still remains. "I keep finding enclaves of old Newcastle, and then an awful shopping centre, that thing that T. Dan Smith [the corrupt mayor of Newcastle in the Sixties] built. Then you walk down Grey Street and it's such an elegant Regency city. It's a beautiful city that's had the heart ripped out of it by people with no class."

Sting always knew he would leave Newcastle. Although he toured schools with a group called Stage Coach and performed in the theatre, there wasn't much scope to earn a living as a musician there. "My professional music career started in the theatre, so this was a kind of coming back to it."

He loves a circular story. Here he is, back where he started and examining where he came from. Sting had a difficult relationship with his father, Ernest, who died of prostate cancer. He was on tour when Ernest died and did not attend his funeral. He didn't go to his mother, Audrey's, funeral either.

"I visited my parents before they died and I said as much as I could say, but didn't go through the ritual of a funeral service, and I regret it. You thought your father never loved you or understood you, and after he died you realised too late he did all along. My father didn't beat me up, but it was a difficult relationship. Yet he had sentimental moments."

Death and dying slip in and out of the lilting, waltzing lyrics to the songs in The Last Ship. Does he work out his fear of mortality in his lyrics so he doesn't have to think about it the rest of the time? "No. I deal with it all the time. I don't live in mortal fear. That's what being 60 is about. You have to deal with the idea that it's finite. You have a certain number of summers left. You don't know how many, but you've lived most of your life. You could be morbid about that. You could also say, whatever's left I'm going to make it count."

His daughter Coco, 21, came up to see the workshop and the Back to Bass show at the Sage, Gateshead. He sang for two and a half hours, and by the end the crowd were all singing Message in a Bottle with him. Is he closest to Coco? He pauses. "She really wanted to see the show. She's very like me. And so is Joe. I suppose because they're both musicians." Joe, 35, has a band called Fiction Plane; eldest daughter Fuchsia Katherine, known as Kate, 29, is an actress. His children with Trudie are Bridget Michael, 28 (known as Mickey), a film-maker and actress; Jake, 26, a film director; Eliot Pauline (known as Coco), who has the band I Blame Coco; and Giacomo. He never felt like a natural father. He has grown closer to his children as they have become more interesting to him as adults, with whom he can have a conversation. "I've never been an ideal father because of my job and because of the way I was parented – it didn't give me any clues about how to do it. But my kids seem to have survived that and they are all great, balanced and hard-working."

Giacomo is still at school. Is he artistic? "He claims he is not. He claims that he doesn't want to be creative because it's not a real job. He says that he wants to be a policeman." There's a deep intake of breath. "OK, fine. We need policemen. I think he's the most eccentric and probably the most artistic of all of us. I think he will happily go the other way; this is his rebellion against a family of actors and musicians, which I can understand."

The romance in The Last Ship is about a reconnection with the girl left behind and I wonder if, in real life, Sting promised someone he'd come back. He bows his head and says to his jumper, "Yeah, of course I did." Where is she now? "Not on the planet. I can't talk about it. It's a long, long time ago."

Another tragedy, another ghost? "Yes, all of them are ghosts. This town is full of ghosts. This is a very rich environment for me, spiritually." He looks up as if he is actually seeing a ghost. Then he laughs. "Maybe there was more than one girl." He looks away again and fumbles. "A lot of people, a lot of dead people around... You get survivor guilt. Why did I survive?" He says guilt is a wasted emotion, yet his new work has been inspired by guilt. When he asks, "Why did I survive?" it's not a throwaway comment. Perhaps, I say, he survived because he's got plenty to say.

He nods solemnly. "I've got plenty to say. I hope so, anyway."

The Sting: 25 Years boxed set (three CDs plus DVD) is available now. His Back to Bass tour returns to the UK on March 16. For ticket and venue information, go to sting.com

(c) The Times by Chrissy Iley

Sting ran away from his home town, Newcastle, to become a megastar, marry Trudie Styler and have six children. And now he's gone back home. The Times' Chrissey Iley joins him for the ride...

On the streets of Newcastle, Sting's home town and mine, the taxi drivers love him. They like him because he doesn't take himself too seriously. They can joke with him, they say, and reminisce. He's a generous tipper, too. Match that with the multimillionaire whose life revolves between homes in Wiltshire, New York, Tuscany and Malibu. The rock star who likes to talk about the intricacies of Tantric sex and pose topless with Trudie Styler, his wife and mother of four of his six children. The environmentalist famous for saving rainforests and offsetting his rather large carbon footprint. You get a picture of a complicated individual.

Before we get to Newcastle, we meet in Paris. He has some free time between gigs and we talk in a darkly lit hotel room in the Place Vendôme. He's just flown in from doing a show in Vancouver. It's winter. Normally, he's tactile, but today we air-hug because he doesn't want to catch my cold. Jet lag is keeping him awake. "I was praying for the daylight. I was first in for breakfast at 6am this morning. I had porridge and coffee." He looks at me suspiciously again. "I cannot get a cold. I cannot work with a cold. I avoid them by willpower. As soon as I stop touring, I'll get a cold. The adrenalin gets you through a show. A cold is difficult." He sniffs theatrically.

Wearing old cords and a cashmere jumper, he stretches his arms in a yawn and reveals a taut yoga stomach. His trousers drop, showing brightly coloured boxers. "You haven't said anything about my hair," he says with mock petulance. His head is shaved. "I like shaving my head. I'm addicted to it. I like the feel of it."

He runs his hand over his stubble and tells me that women come up to stroke him like a dog, and then he laughs at himself.

"So, here we are, being flagrant," he says. Flagrant is a good word for him. He's a consummate flirt, and he loves to perform. He seems to be on a perpetual tour. Last year it was the Symphonicities tour with the Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra, all sweeping keyboards and lush melodies. Now it's the Back to Bass tour, the other extreme: no keyboards, his bass guitar, a couple of violins, percussion. He's touring Europe with it and returns to the UK this month. It's called Back to Bass because that's his instrument and, in the Seventies, he redefined how a rock band should sound thanks to his bass playing.

Is he addicted to being on the road? "It's a lovely feeling. You're out in front of 5,000, 10,000 people and everyone's pleased to see you. It's hard to replace that," he says. "And it's also hard to express how wonderful that feels. Everything seems amplified by the lights and the occasion. Am I addicted to it? Probably. I don't like staying in a city too long. Tomorrow is somewhere else. Let's move."

You wonder, of course, about all this moving about, what it is he's running from. Running has been a constant in his life. He ran from Newcastle to form the Police. He ran away from the Police when they were one of the world's most successful bands in the early Eighties. He didn't tell the band it was over. Perhaps because it wasn't. Years later, in 2007, they reformed. They finally got closure. "You can abandon something; you can never finish it. Relationships are never finished."

He ran from his first marriage, to actress Frances Tomelty. It imploded in 1982 when he fell in love with his neighbour, Trudie Styler. At the time, he thought Styler looked like a "damaged angel", yet he credits her with turning around his life. "She is my orbit. She is my central point. She grounds me. It is important to me that I have something to orbit. Is she a sun or a moon? I don't know."

He's mostly found in New York, where his youngest son, Giacomo, 16, goes to school. "Trudie is based there and I circle her. The circle can be huge, but I have to have somewhere to think of as home, and that's her. She's coming to Paris. We'll go to dinner. I haven't seen her in a month." He exhales loudly, mournfully. "It's hard, but it keeps it juicy. It keeps it romantic. She'd be sick to death of me if I were around all the time." Would he be sick of her? "No," he laughs.

She seems almost an idol to him: the strong woman, the mother, the lover. "She's pretty good at all of those, I have to say."

He seems to enjoy long-distance marriage. Is that because that's how he knows how to feel love, by separation? "Mm," he nods, giving a jet-lagged yawn. "I'm not punishing myself. She does have her own orbit. She has far more jobs than I do. We orbit in tandem, really. But we mentally think each other is home."

The couple were recently shot for Harper's Bazaar – scantily clad, on a bed, kissing, dishevelled. What possessed them? "That was fun!" he replies. "Aren't we allowed to have fun?" He smiles. "There was a lot of outrage and it was just a photo spread. I couldn't take it seriously. We looked good," he laughs. "And that's what annoys other people."

Over 30 years together, their relationship has changed, he says, but they have both changed in complementary ways. "I always encourage her to take on challenges and to work. That's very important to Trudie and me. I never wanted to be going back to the little woman, because I'd be bored by that, but she does so many things. She's an actor, producer, she runs businesses, she edited The Big Issue the other week... She's an incredibly accomplished woman and I'm proud of her. She always steps up to a challenge."

He tells me the ambiguity of love means that Styler could have equally destroyed him as opposed to making him whole. What does he mean? "A lot of relationships begin with an emotional prenuptial where you say, ‘I love you this much, but not enough that I could be destroyed.' That's where a lot of relationships fail. You have to take that risk. You have to give your whole self, everything, so you could be destroyed by it, totally. And the other way, too. If she leaves me, if I leave her." Could that happen? "Of course it could happen. Life's full of surprises. We talk about stuff. We have a deep connection, which we renew on a daily basis. We're not complacent about our relationship at all. It's not that we're insecure – it's just that we know what the reality is. Most marriages end in disaster. It's unusual to have a long relationship and we have a very long relationship. I want to continue it."

It's important to him never to take anything for granted. On the whole, he likes to work at things, be it relationships or songs. For a long time he was devastated about the breakdown of his first marriage. He was quite undone by it, and revisited that sense of loss in his songs. "It's the only thing I've ever failed at." When Sting was Gordon Sumner, bus conductor or tax officer, he worked hard, even though he knew he was a misfit. "I was terrible," he says of the tax collecting. "I was fired and never wanted to work in an office again. I'd also been on the dole, which I hated. I just couldn't do it."

He's just written a musical, The Last Ship, inspired by the life he ran away from when he left Newcastle in 1977. The son of a milkman and a hairdresser, he grew up in the shadow of Swan Hunter, the shipyard on Tyneside. Sting is a contradiction: he wants to move forward, but he's haunted by his upbringing, and it's to those dark places he goes for inspiration. The Last Ship, about leaving Tyneside and coming back, is about a man's need for work, community and love, and about what happens when you take work away. He's written some new songs for it and also uses a couple of moving old ones. His old friend Jimmy Nail, of Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, will star, but it's still early days and he's not sure if it will premiere on Broadway, in London or in Newcastle.

The musical is Sting's tribute to where he grew up, to the people of the North East. "I'm very inspired about it. More inspired than I've been perhaps for a long time. I think it's about what happens when work ends. What happens to communities and how important that is. It's about how people were ambivalent about that job. They think it was a hard job in the worst industrial conditions in Europe, and yet what they built, they were very proud of. They built the biggest ships in the world in that town, and when that disappeared it was a huge thing. That's what the play is about.

"We don't make anything any more. The idea of making things with your hands is important to us, especially men. I work with my hands every night, with an instrument. It's physical work. When you take that away from a community, what do you replace it with? That's the backdrop for the play, but it's also a love story, a redemption."

A few months pass and I go to Newcastle to watch a workshop of The Last Ship. Sting has been in the city all week rehearsing and it takes place in a tiny arts theatre near the Quayside, close to where Sting first performed, pre-Police, with the band Last Exit. In recent years, he's been increasingly drawn back to his childhood home. It started with his 2009 album If On a Winter's Night…, which featured traditional Northumbrian folk songs and the local pipe player Kathryn Tickell; a televised performance was held in Durham Cathedral.

The next day we are at the Malmaison hotel, overlooking the bridges that define the Tyne. Sting has just had breakfast with Jimmy Nail, who calls him Gordon. Does he do that to annoy him? "Yes, a little bit. Nobody else calls me Gordon," he says. "I've known Jimmy 20 years. I can't imagine the show without him. He's very excited; he loves the material and his voice is incredibly raw."

We order espressos. "I was brought up in the shadow of the shipyards. I was fascinated and terrified by them at the same time and wondered where I would fit in. That was the landscape of my dreams. Writing songs for other characters to sing freed me up, and I feel very fertile because of that. You can get paralysed, and I can get in my own way. I hadn't written a song for a long time and in the past year I've written 25. I think you have to write when you feel like writing. When something needs to come out. It's not the kind of job where you just turn it on."

The idea solidified in his head after he read about a shipyard closing in Poland, where a priest began to raise money for a charity to start building ships again to give the men something to do and their dignity back. "It struck me as Homeric – an exciting, crazy idea which actually happened. I thought if I welded that inspiration to the story of my town to make it more allegory than history it might work, and there'd be a good message, a universal message that people need to work.

"One of the most depressing times in my life was signing on on a Wednesday afternoon. I felt demoralised and defeated. I couldn't bear it. I understand what it's like not to have work. I was still a musician. I always had that. Not to have work, it destroys people."

The story is set in the early Thatcher years, which saw the decline of the mining and shipbuilding industries in the North East. "If you have no work and you don't know what's happening next, where's the future? How can we look after our kids? The economic system is falling apart. What do we have left? We have community. The other night, a bloke in the audience said there's something special about Newcastle. There's a spiritual connection with this place. It's not dewy-eyed, sentimental nostalgia. This town is genuinely loveable, with its own river and football team. I don't know another region of England that has this feeling. So coming back, having been away so long, I think I see it more clearly."

He's been walking around the city, exploring the streets that he grew up in with his siblings, Philip, Anita and Angela, navigating a path between what's lost and what still remains. "I keep finding enclaves of old Newcastle, and then an awful shopping centre, that thing that T. Dan Smith [the corrupt mayor of Newcastle in the Sixties] built. Then you walk down Grey Street and it's such an elegant Regency city. It's a beautiful city that's had the heart ripped out of it by people with no class."

Sting always knew he would leave Newcastle. Although he toured schools with a group called Stage Coach and performed in the theatre, there wasn't much scope to earn a living as a musician there. "My professional music career started in the theatre, so this was a kind of coming back to it."

He loves a circular story. Here he is, back where he started and examining where he came from. Sting had a difficult relationship with his father, Ernest, who died of prostate cancer. He was on tour when Ernest died and did not attend his funeral. He didn't go to his mother, Audrey's, funeral either.

"I visited my parents before they died and I said as much as I could say, but didn't go through the ritual of a funeral service, and I regret it. You thought your father never loved you or understood you, and after he died you realised too late he did all along. My father didn't beat me up, but it was a difficult relationship. Yet he had sentimental moments."

Death and dying slip in and out of the lilting, waltzing lyrics to the songs in The Last Ship. Does he work out his fear of mortality in his lyrics so he doesn't have to think about it the rest of the time? "No. I deal with it all the time. I don't live in mortal fear. That's what being 60 is about. You have to deal with the idea that it's finite. You have a certain number of summers left. You don't know how many, but you've lived most of your life. You could be morbid about that. You could also say, whatever's left I'm going to make it count."

His daughter Coco, 21, came up to see the workshop and the Back to Bass show at the Sage, Gateshead. He sang for two and a half hours, and by the end the crowd were all singing Message in a Bottle with him. Is he closest to Coco? He pauses. "She really wanted to see the show. She's very like me. And so is Joe. I suppose because they're both musicians." Joe, 35, has a band called Fiction Plane; eldest daughter Fuchsia Katherine, known as Kate, 29, is an actress. His children with Trudie are Bridget Michael, 28 (known as Mickey), a film-maker and actress; Jake, 26, a film director; Eliot Pauline (known as Coco), who has the band I Blame Coco; and Giacomo. He never felt like a natural father. He has grown closer to his children as they have become more interesting to him as adults, with whom he can have a conversation. "I've never been an ideal father because of my job and because of the way I was parented – it didn't give me any clues about how to do it. But my kids seem to have survived that and they are all great, balanced and hard-working."

Giacomo is still at school. Is he artistic? "He claims he is not. He claims that he doesn't want to be creative because it's not a real job. He says that he wants to be a policeman." There's a deep intake of breath. "OK, fine. We need policemen. I think he's the most eccentric and probably the most artistic of all of us. I think he will happily go the other way; this is his rebellion against a family of actors and musicians, which I can understand."

The romance in The Last Ship is about a reconnection with the girl left behind and I wonder if, in real life, Sting promised someone he'd come back. He bows his head and says to his jumper, "Yeah, of course I did." Where is she now? "Not on the planet. I can't talk about it. It's a long, long time ago."

Another tragedy, another ghost? "Yes, all of them are ghosts. This town is full of ghosts. This is a very rich environment for me, spiritually." He looks up as if he is actually seeing a ghost. Then he laughs. "Maybe there was more than one girl." He looks away again and fumbles. "A lot of people, a lot of dead people around... You get survivor guilt. Why did I survive?" He says guilt is a wasted emotion, yet his new work has been inspired by guilt. When he asks, "Why did I survive?" it's not a throwaway comment. Perhaps, I say, he survived because he's got plenty to say.

He nods solemnly. "I've got plenty to say. I hope so, anyway."

The Sting: 25 Years boxed set (three CDs plus DVD) is available now. His Back to Bass tour returns to the UK on March 16. For ticket and venue information, go to sting.com

(c) The Times by Chrissy Iley

Comments

2

March 12, 2012

posted by TarAncalime

Take this Michael Pilz;-)))

I just want to shove down that lovely interview down that stupid Michael Pilz' throat in Die Welt newspaper! Ha!

March 11, 2012

posted by caroguzzi

Love It

What a pleasure to read this article,, Thank you Chrissy Liey for writing it :o)

Newer comments 1 - 2 of 2 Older comments