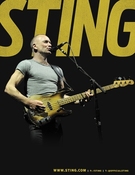

Sting, the tireless troubadour - reports The Washington Post...

December 04, 2014

Night after night, as the lights go down in the Neil Simon Theatre and musicians on guitar and flute and fiddle begin to play, a multiple Grammy-winning international star settles into a seat in a back row and drinks in anew all the Broadway sights and sounds.

It's the closest that a guy named Sting will ever get to the life of an average Manhattan commuter.

"I watch it every day," says the 63-year-old singer-songwriter, still in possession of the sleek build of a rock sensation half his age. "I'm fascinated by the process and the actors making this story and the songs their own. I'm fascinated by the audience and how they react. I sit way in the back in the dark, sort of a phantom, and l leave before the lights go up."

The event he's stuck on is one of out his own dreams: "The Last Ship," a musical allegory set in Newcastle, the hardscrabble, post-industrial English seaside city of his youth. The $15 million show, featuring a 29-member cast as little known as Sting is world famous, marks his first try at composing a musical, one that has taken on the proportions of an intensely emotional, deeply personal mission.

That he might want to find some way to separate himself is supported by the numbers: Since the mixed reviews that arrived after its Oct. 26 opening night, "The Last Ship," with its 20 Sting songs, has lost about $75,000 a week, according to its lead producer, "Rent" veteran Jeffrey Seller. Such a statistic is usually the death rattle for a Broadway production. To Sting, though, it was a call to action. Putting his star power further on the line, he is relinquishing his nightly seat in the dark for a perch up front and in the spotlight. In hopes of saving the show, he is joining it.

So on Tuesday, after being feted this weekend as one of the year's Kennedy Center Honorees, Sting will for the first time step into this Joe Mantello-directed musical, replacing his old friend Jimmy Nail, whom he lobbied to accept the featured role of Jackie White, a shipyard foreman who leads a band of unemployed workers on a quixotic boat-building quest. The box office will no doubt boom during the weeks he plays Jackie. Still, he has to depart in late January, as he's committed to a concert tour of Australia and Europe with his friend Paul Simon.

The uncertainty is, will his short residency be enough to turn the tide? Can Sting make "The Last Ship" last?

"It's one of the most important projects of his life, without question," says his manager, Kathryn Schenker, who has worked for Sting for 35 years. "The guy's a fighter. He couldn't live with himself if he did not give it every opportunity to live on."

The war footing is confirmed by Sting. "I'm fighting a battle, and I will fight tooth and nail for this," he says during a late-morning conversation in the belly of the Neil Simon Theatre, where "The Last Ship" is running. He will allude to his battle readiness again and again, although his genteel tone is absent the menace he projected as the sexually dangerous, platinum-haired frontman for the Police. The post-punk New Wave rock trio he created with Stewart Copeland catapulted him to wealth and fame in the late 1970s and early '80s, with such hits as "Roxanne" and "Every Breath You Take."

You do have to wonder why, at this comparatively advanced stage of his career, he needs what some might regard as the aggravation of a musical on Broadway, a complexly collaborative form in which so much is out of a musician's control. He's a father six times over and a granddad several times, too — "Grandpa Sting"? — with enough money and causes (notably, his Rainforest Foundation) to occupy a whole hive of Stings. He even has a CBE from the queen, for goodness sake — the precursor to knighthood. Plus he still gets a big kick out of the vagabond life of a rock star: "I enjoy the hurly-burly of it, the peripatetic nature of it," says this onetime schoolteacher with the impressively posh vocabulary.

Simon, Sting's upstairs neighbor in New York, had his own original musical on Broadway nearly 20 years ago, the tepidly received "The Capeman"; when Sting talked to him about "The Last Ship" — which Simon has seen twice — the older songwriter offered him some advice about maintaining distance from the show. "Don't tie yourself to the front of the train," Sting quotes Simon as warning.

That, apparently, wasn't going to work for Sting.

"I have no choice," he says. "I have to be in the front of the train."

It's in Sting's competitive DNA to tow his "Ship" to safety. Maybe a bit of arrogance is built into this stubborn pursuit, or the appearance of it; though he sometimes strikes fans as aloof, his longtime aides say that no one is more loyal, or dependable. But this is also a labor occasioned by a lifelong sense of unfinished business.

Inspired by his early memories — not the least of which are of Rodgers and Hammerstein albums as the background music of his childhood — the show and its evocations of wayward sons and tense households are linkages to a past he's still grappling with. "I couldn't have prophesied the emotional impact of this play both on myself and on audiences," he says. "I think much more than perhaps I intended."

Raised just outside Newcastle in Wallsend, a rough-hewn English town with ruins dating from the Roman empire, Sting — né Gordon Sumner — grew up the oldest of four children of Ernie Sumner, a stoic milkman, and his more vivacious but restless wife, Audrey. His ancestors worked in the shipyards, which loomed in his early life as places that were "toxic, dangerous, noisy, frightening."

He said as much in "Broken Music," his keenly observed 2003 coming-of-age memoir that presages the themes of his musical. "The ships leaving the river," he wrote, "would in hindsight become a metaphor for my own meandering life, once out in the world never to return."

It was the success of the Beatles, whose stories of working-class upbringings in Liverpool resembled his own; the gift at age 11 of an uncle's hand-me-down guitar; and a copy of "First Steps in Guitar Playing," by Jeffrey Sisley, that set him on a tuneful path. "This book will teach me how to tune the heirloom guitar and introduce me to the rudiments of strumming chords and reading music. I'm in heaven," Sting recalled in his book. (He was given his famous nickname at age 21 by Gordon Solomon, leader of a group he was playing with at the time, the Phoenix Jazzmen, who decided a black and yellow sweater that Sting wore reminded him of a bee.)

"I had a dream about being a successful musician," Sting says now. "Where that confidence came from, I do not know. But I had it for a long time. If you dream something hard enough, it will tend to happen. I think I got lucky. And then you have to get smart real quick."

Sting was a tax clerk, a teacher or simply on the dole in the years he spent as a struggling singer and bass player, in bands doing gigs for pittances in the towns in the English north. In 1976, he took a chance, moving with his then wife, budding actress Frances Tomelty, and their baby, Joe, to London. (He's been married to second wife Trudie Styler for 22 years.) Copeland, an American drummer living in London, had heard him play once, Sting recounts in the book, and told him to drop by if he ever was in the city. That contact would set in motion the creation in 1977 of the Police, with guitarist Andy Summers joining them soon after.

With Sting writing their songs, the Police became a global phenomenon, touring the world, winning awards and producing five studio albums and a slew of hits, among them "Message in a Bottle" and "Don't Stand So Close to Me." They were also growing apart, with Sting establishing a presence as an actor in movies such as "Quadrophenia" (1979) and "Plenty" (1985). By the mid-1980s, they had split, a dissolution so unpleasant that Rolling Stone magazine took note of it in an article last year titled "The 10 Messiest Band Breakups."

On the way up, however, Sting had found his lyrical voice. The Police had charted a course, under the influences of musical sources as varied as rock-and-roll and reggae, and guided, too, by Sting's instincts for dark romance. One song that became a signature was inspired by a poster Sting saw one night in his Paris hotel, for a production of Edmond Rostand's "Cyrano de Bergerac." He'd come across it after walking by some ladies of the evening, and somehow the name of a character from the work became fixed in his mind and set his imagination alight.

"I will conjure her unpaid from the street below the hotel and cloak her in the romance and the sadness of Rostand's play," he wrote, "and her creation will change my life."

The name, of course, was Roxanne.

‘I like to create earworms," Sting is declaring, in the bowels of the theater on West 52nd Street. "I like people sending me e-mails saying, ‘You bastard, I can't get that f------ tune out of my head.' Something's working? Play it again!"

The title song of "The Last Ship" is one of those insistent melodies. It achieves earworm status because it's infectiously redolent of "the modal folk music of my region," as Sting puts it. And because, during the 21/2-hour musical, it's played no less than four times.

Perhaps the fight for the musical is also such a crucial one for Sting because "The Last Ship" has irrigated a creative desert for him, the longest dry songwriting spell of his career.

"What preceded the writing of this musical was an eight-year period of not writing songs. A fallow period," he says. "I had them before but never to this extent, which began to worry me. I mean, songwriting is a kind of therapy anyway: You're digging stuff up. I felt I needed some therapy. Regression therapy is what I landed on, going back to my childhood, which was not particularly happy, dredging up stuff that perhaps I would have kept suppressed if I'd had my druthers.

"But there wasn't any choice. There was a compulsion to tell this story and once I decided to do it, it was as if the songs had been kind of stuck there for a long time, almost fully formed."

"The Last Ship" began its voyage several years ago after Seller, the producer, dined at Schenker's house, and she mentioned Sting had entertained ideas of returning to Broadway. Back in 1989, he starred as Mack the Knife in a revival of "The Threepenny Opera"; he and the production were savaged by Frank Rich in the New York Times. ("I was in full rock star flight. I didn't give a f---!" Sting says, laughing. "I think I'd be much more cautious, you know, now.")

A couple of months after that dinner, Seller says, Schenker called, reporting that Sting had read a newspaper story about the Gdansk shipyard, the site in Poland made famous in the 1980s by Lech Walesa and the workers of the anti-Soviet Solidarity movement. She told him, " ‘He's inspired to somehow make a musical about those men, but make it about his home town,' " Seller recalls. "I said, ‘I'm in.' "

After a lunch meeting with Seller, Sting says, "I went back to my apartment on Central Park West, sat down with a notepad and wrote the names of the people I knew, people I went to school with."

Verses poured out of him, and the basics of the show were laid out, "all in one afternoon. Reams and reams." (Two veteran writers for the stage, Brian Yorkey and later John Logan, would work on the show's script.)

Having poured his heart into the music, Sting is now going to sing it nightly, sing it for his own pleasure, an audience's curiosity — and the suppers of everyone in the production, people he's come to care about. "I enjoy having hits," he says over the phone a couple of days after his starring gambit has been announced. "I'd rather have a hit against the odds than a hit that obeys the formulaic rules. This is exactly the play I wanted to put on. It may be difficult, it may be ugly, but it's the one I wanted to do."

The battle goes on.

(c) The Washington Post by Peter Marks